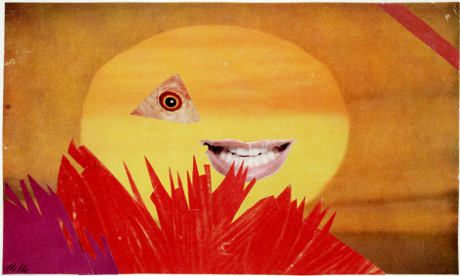

Looking at the clamorous photomontages of Hannah Höch is always a slightly overwhelming – albeit eye-opening – experience.

Here the viewer is tasked with navigating visual planes littered with references to everything from heads of state and showgirls to lipstick, finance and fatherhood culled from the popular press.

Born in the German town of Gotha in 1889, Höch learnt her trade as an artist in Berlin where, in 1919, she joined her then partner Raoul Hausmann, as well as George Grosz, John Heartfield and Johannes Baader in becoming a member of the left-wing, avant-garde Berlin Dada Group.

In the incendiary interwar years, Höch’s carefully crafted works cut a metaphorical knife through the dizzying contradictions of rampant consumer culture, bloated German militarism and the ambiguous role of women.

A new exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery is dedicated to her career, spanning six tumultuous decades from the 1910s to the 1970s. It is the first major retrospective of Höch’s work in the UK and a testament to the current groundswell of interest in this most intriguing of creative forces.

“I think she was an artist who truly realised the political and poetical potential of images, what I would call the further realms of images as a counter-cultural force,” says exhibition co-curator Daniel Herrmann.

“Her rambunctious spirit and rebellious nature saw her produce acerbic, socially and politically engaged imagery, transforming the means of working with collages, abstraction, materiality and challenging the construction of beauty.”

Höch combined new modes of seeing such as aerial photography and microscopy with embroidery patterns and snippets from trashy magazines to dissect the much-hyped construct of the sexually liberated, working ‘New Woman’ of the Weimar Republic.

It is perhaps her uncanny ability to expose the ironies behind the subtle (and not so subtle) manipulation of images of women for various commercial and political ends – served, albeit, with a thick slice of ambivalence – that strikes with such poignancy today.

Take for example her short essay The Painter (c.1920), a wonderfully witty take-down of the myth of the male artist genius involving an abstract painting, a row about whose turn it is to wash the dishes and a bunch of chives.

In her most famous work, Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919-20), there are cut-out words from newspapers among the wheels and cogs of the slick new machine culture alongside dislocated pieces of architecture and animals.

Look closely and you’ll find Marx and Lenin and a tiny map of Europe illustrating countries where women had the right vote. At the centre of it all, the decapitated body of dancer Niddy Impekoven pirouettes elegantly beneath the floating head of artist Käthe Kollwitz.

In High Finance (1923), a double-barrel shotgun, the black, white and red flag of the German Reich and English chemist John Herschel are deployed to critique the relationship between financiers and the military in a disastrous period of economic crisis.

More than most, Höch was acutely aware of the painful gap between public rhetoric and private reality.

During the Second World War, Höch was blacklisted by the Nazis who included her work in the notorious Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich in 1937. Höch survived the war by retreating to a remote house on the outskirts of Berlin and a period of “lyrical abstraction”.

Höch continued to produce works until her death in 1978 and the exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery offers a rare chance to get up close with over 100 collages, photomontages, watercolours and woodcuts from various stages of her career, examples of which are, sadly, so few and far between in British collections.

Hannah Höch is at the Whitechapel Gallery, 77-82 Whitechapel High Street, E1 7QX from 15 January – 23 March