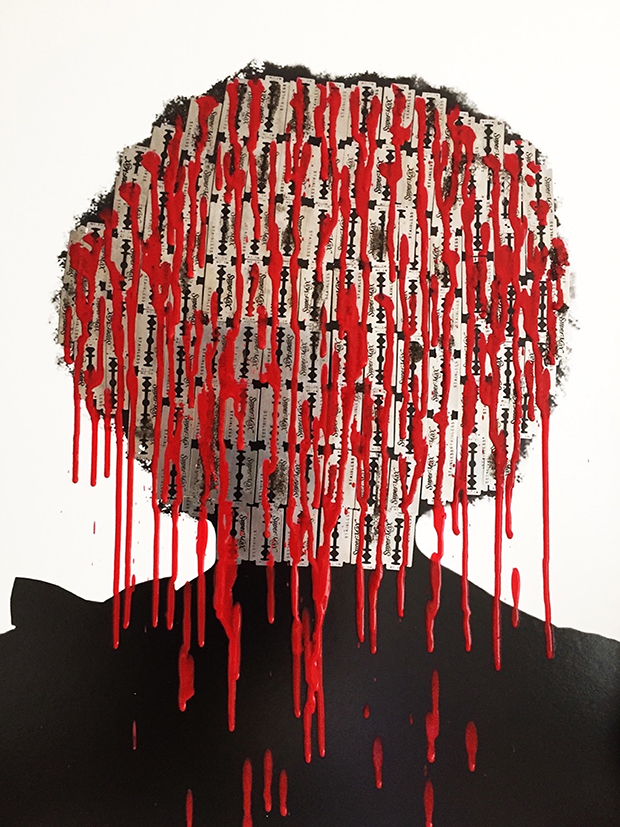

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is the focus of Aida Silvestri’s new photography exhibition in Shoreditch.

The practice, in which parts of a girl’s genitalia are cut off for non-medical reasons, often in the belief that it will control their sexuality, is still taboo in many parts of the world and frequently ignored by the media.

“I had another project about migration that had lots of coverage in the arts world. But when it comes to this [FGM], they don’t want to know.

“People are not comfortable looking at FGM images. Some say they are a little bit too harsh, but that is just an excuse. We need to be bold if we want to raise awareness,” said Ms Silvestri.

In the midst of Shoreditch’s Friday evening revellers, six women from the fields of art, health and advocacy met at Autograph ABP gallery to discuss ongoing efforts to eradicate FGM.

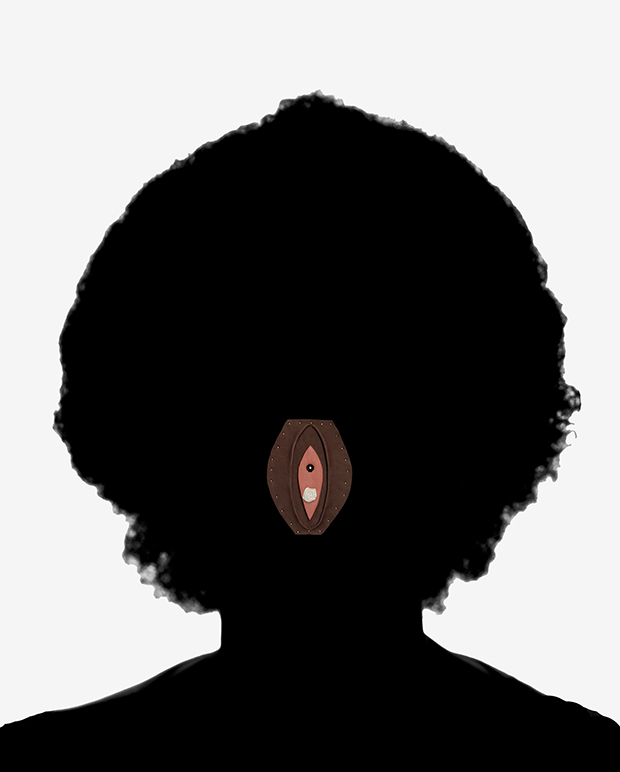

The panel, which attracted a 50-strong audience, was part of Silvestri’s Unsterile Clinic exhibition, a collection of photographs inspired by the artist’s personal experience.

Her silhouettes of FGM survivors feature layers of hand-stitched leather showing the type of mutilation they suffered.

Each portrait is accompanied by a poem, with the words edited from the subject’s own, moving story.

In an interview prior to the panel, Silvestri, who was born in Eritrea but now lives and works in London, said that knowledge of FGM has improved in the UK.

She said: “I had my first child in 2011 and nobody knew about FGM. Even though some [health workers] should have been aware, nobody said anything to me.

“And then, with my second pregnancy, I was asked if I had undergone FGM. I said I had, and was then sent to be checked.

“So the awareness has greatly changed, and health centres and specialist clinics dealing with FGM are doing a lot of work to raise that awareness.”

However, Silvestri still encounters a lot of “ignorance” from people regarding her work.

She recalled a lady at a summer festival last year, who, when confronted with her art, said: “This isn’t our problem, this is the migrant’s problem. This is a Muslim problem. We Christians wouldn’t do that.”

The experience showed Silvestri, who is Christian herself, that people still don’t understand how widespread FGM is.

It is practised around the world, including in Africa, South America, the Middle East and the Far East, by communities of various races, religions and traditions.

“It is everybody’s problem,” Silvestri explained.

But she admitted that the subject matter had made it difficult to attract attention from mainstream media.

Education, the artist argues, is the way forward.

“I think we need to educate more people, and it has to start in school. The government has now included FGM as part of its safeguarding, so everyone has to know about it.

“During an Equality and Diversity workshop that I have attended recently, it was discussed that Ofsted apparently downgraded one school because the dinner lady didn’t know what FGM meant, which is really good, but we need to do more.

“More than prosecutions, we need education and support.”

Silvestri is planning more events to get people talking about FGM: “I’ve started a fight and I won’t stop.” And she is calling on councils to engage with locals and do more to teach youngsters about the practice.

It was a view echoed by her fellow panellists later in the evening.

Many issues surrounding FGM were raised during the three-hour debate: the patriarchal society within practising communities. The fact that FGM is an economically lucrative crime. The lack of clear guidelines for treating victims. The dearth of follow-up services, both psychological and physical, in the NHS.

But one message in particular rang out loud and clear: that the key to ending FGM is educating children and practising communities about its effects, as well as providing better training for teachers and health workers.

Deqa Dirie, health advocate and anti-FGM campaigner, said: “I’m not bashing anyone, but I know women who have been severely damaged by health professionals in the UK.”

She called for more follow-up services for survivors in the NHS and said nurses and midwives need to be better equipped to deal with survivors.

Emma Boyd, a senior producer at Animage Films, explained how the company works with UK charity FORWARD to produce short films for its FGM campaign.

Boyd said they were focused on getting their message into primary schools. She introduced an animation called The True Story of Ghati and Rhobi, which is played to children across Tanzania to raise awareness of FGM. FORWARD is hoping to adapt the film into a variety of languages.

Dianna Nammi, who founded the Iranian and Kurdish Women’s Rights Organisation (IKWRO), agreed that “talking to communities stops people doing it [FGM].”

IKWRO has launched the Right to Know campaign, which aims to get honour-based violence, including FGM, on the national curriculum in the UK.

Hoda Ali, a nurse and trustee of the 28toomany charity, spoke passionately about the merits of education.

Ali survived Type 3 FGM, which involves sealing the vagina until only a very small opening remains, and said it “took away her chances of being a mother.”

She was constantly in hospital from the age of 11 because her injuries meant her periods accumulated in her uterus. She was 17 years old when she had her first period.

She said: “My nieces are eight and eleven, and they’re at the back tonight because they’re not too young to listen. And they will go into school and educate their teachers.”

Ali also called for Silvestri’s work to be used at clinics, so women who have difficulty communicating with health workers can point out what type of FGM they have.

There was controversy when a teacher in the audience asked whether compulsory medical examinations at schools should be reintroduced so cases of FGM are caught early.

Hilary Burrage, author and chair of the debate, initially agreed, but her fellow panellists rejected the argument out of hand, saying it would do nothing to prevent FGM.

A suggestion was raised that midwives should be trained to explain to mothers, before they leave the hospital after giving birth, the law regarding FGM and its impact on victims. Again, the emphasis was on training and education.

The experts agreed that no amount of prosecutions or early diagnoses will end FGM: only when people are taught about the consequences of the practice will it stop.

Aissa Edon, a specialist midwife at The Hope Clinic and a survivor of FGM, described the moment she confronted her family: “I sat my father down, and I didn’t accuse him of child abuse. I explained to him the consequences that I have to live with every day,” she said.

“My father cried and simply said, ‘I didn’t know.’ And then he promised that no more of the girls in our family would ever be forced to suffer as I did.”

Unsterile Clinic

8 July – 17 September 2016

Autograph ABP

Rivington Place (off Rivington Street)

London

EC2A 3BA