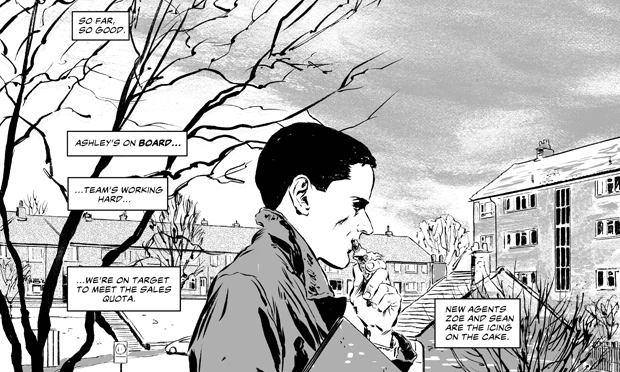

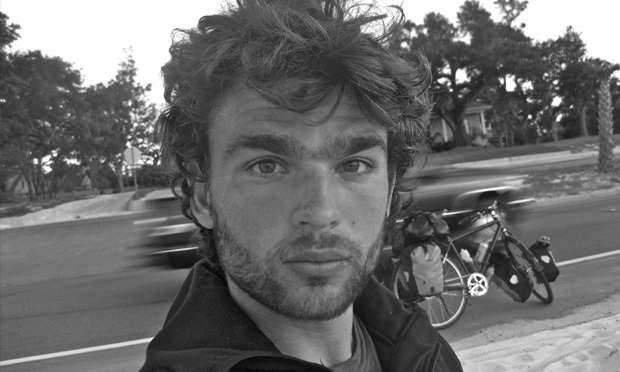

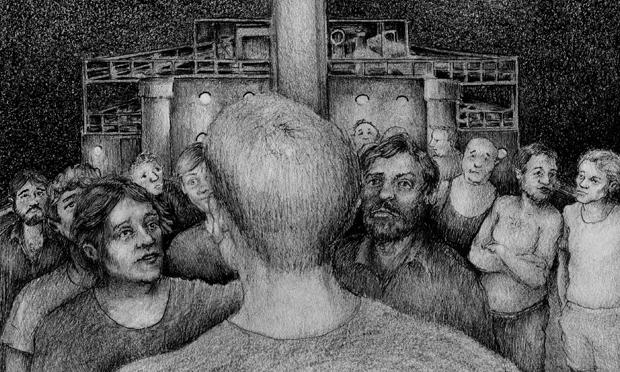

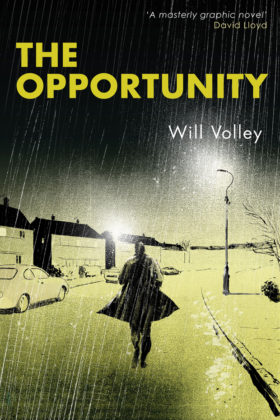

Multi-level marketing, sometimes known as pyramid selling, may not strike most people as a gripping subject for a debut comic noir. But then Will Volley is not most people. After publishing graphic novel versions of Romeo and Juliet and An Inspector Calls, the 35 year-old took a year off work, moved back home and wrote his own comic.

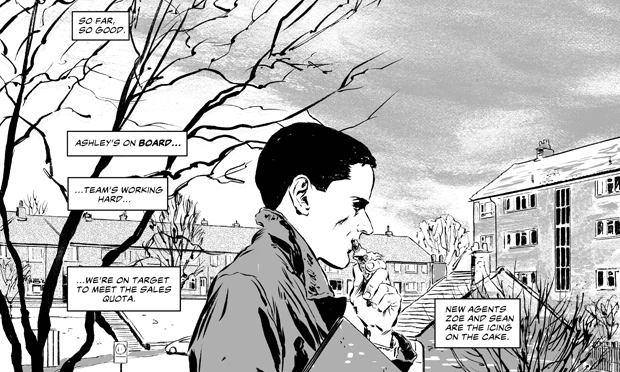

The Opportunity is about Colin, a successful door-to-door salesman on the verge of getting his own sales office. One day everything changes and Colin’s sales team is given a new all-or-nothing target, and only five days to achieve it in.

Volley explains why door-to-door sales made such a good subject, the Stoke Newington schoolteacher who inspired him and the fallen footballer he’s covering in his next novel.

How much of this story was drawn from your own experience?

My experience in a multi-level marketing company was limited to about two or three weeks. I enjoyed it – being a navel-gazing art student and coming into that climate was great because it was different, and the people there were enthusiastic. But there were things about this company that didn’t make sense: all the staff lived together in the same flat and it felt a bit like a cult. Through research I found support groups online for people who’d worked in this company, and then I devised a plot from interviewing ex-managers.

Did you ever worry about how you were going to make a gripping thriller about multi-level marketing?

No! When I was working there I thought: this is the perfect premise for a story. But it took me a while to come up with a plot I was satisfied with.

How’s the political landscape and the job market changed since you worked for this company?

It’s the same. A funny thing happened when I had literally just finished the book. I got a knock on the door, got up from my desk and went downstairs, and there was this young salesman. His pitch was word for word the same one I used ten years ago. Talk about weird.

So I sort of cut him short and said, look, you need to be careful. He looked startled. I felt bad about it because he looked disappointed. Young people want to be optimistic and they offer incredible loyalty. That’s what this company provides: it gives you a thick blanket of security and the managers big you up. It’s hard to say how common these types of companies are now, but at the book launch someone came up to me and said they had spent a day with these guys in Tottenham.

You mentioned in another interview that one of your teachers brought Daredevil comics into school.

That was a real turning point. I went to William Patten Primary School and I had a teacher who was an ex-punk. He introduced me to weird things you wouldn’t expect kids to read and seeing that artwork by that specific artist changed everything for me. I fell in love with it and my own drawing just kind of grew from there.

What are you working on next?

A story about an ex-footballer who turns to a life of crime. I read a statistic that 40 per cent of ex-footballers go bankrupt within five years of their career ending. Football’s all they know and if they’re trying to maintain their lifestyle lots of them end up gambling, getting into debt and some even go to prison. It’s going to be much more personal: another falling from grace story, but this time a redemption tale.

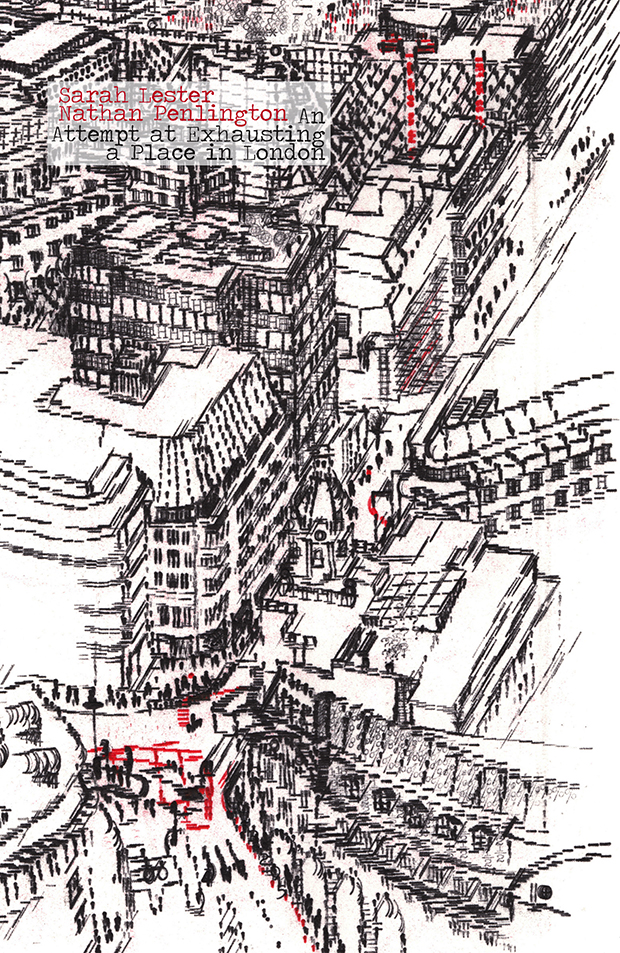

The Opportunity is published by Myriad Press. ISBN: 9781908434791.

RRP: £12.99. Volley will be signing copies at the East London Comic Arts Festival (ELCAF) on 11 June.