John Michael McDonagh’s Calvary is at once raging and solemn. It rushes back and forth between the two states to dizzying effect, washing through its 101 minutes like the crashing waves of Ireland’s west coast sea, on which the film’s central, and sinful, parish rests. It’s a darkly comic musing on the fragmentation of an uprooted society and its most famous – or infamous – institution, the Catholic church. For all its splendour, though, there is something amiss, something distinctly Irish.

The film opens to a shadowy confession-box exchange between Brendan Gleeson’s Father James Lavelle and a troubled parishioner, who promises to kill the good priest in vengeance for the sexual abuse he suffered as a child. He gives Lavelle a week to put his things in order before a high noon-style showdown on the waterfront. “Killing a priest on a Sunday,” he says – “that’ll be a good one.”

The early scenes often slide into stunning overhead shots of County Sligo, evoking something of Ireland’s champion of religious critique, novelist John McGahern, who was born in the adjacent County Leitrim and would set many of his bruising portraits of rural-Catholic life in the wilds of the bordering Roscommon. It’s an evocation that I couldn’t shake off for the entire film, doing McDonagh something of a disservice.

A striking difference between the director and McGahern lies in the latter’s tender handling of a fading way of life. Despite the scathing nature of his work, the author would delicately lament the loss of elements of the farming communities of which he wrote. It’s not that McDonagh’s work is off the mark in turning its back on local identity, it’s that there is too little of McGahern’s fascinating Ireland left for my liking, beyond the rolling hills and tattered reputation of the ailing church.

This is perhaps the result of the 20-plus years that have passed since the author’s thumping Amongst Women was nominated for the Booker Prize, with the generational shift leaving too little of that past to justifiably cling on to. Not one of McDonagh’s characters appears to belong, and while this is intentional, and affective in its own right, the absence of history leaves a gaping hole – for me anyway. The film’s gorgeous sounds and images suffer from a kind of hollowness as a result. Even Lavelle is an outsider, drafted onto the land that was once every bit a part of its inhabitants – for better or worse. The majority of Calvary’s figures are displaced and at a loss; it’s a bankruptcy that is a harsh but honest reflection of the times.

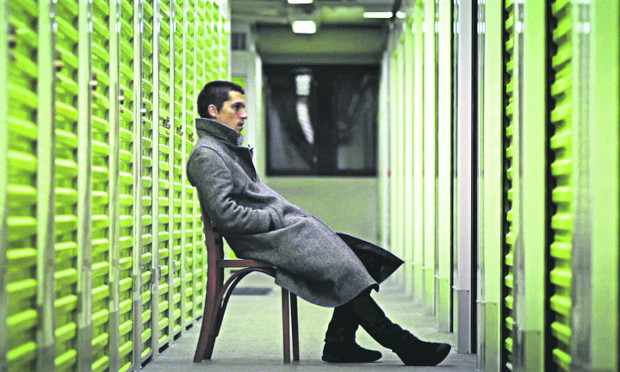

This half criticism is based on a personal grievance and should take little away from the film’s considerable merit. Gleeson is sublime as the widower priest, who, to begin with, looks only mildly perturbed by the murderous threat hanging over his head. Recovering from alcohol addiction and offering counsel to his damaged visiting daughter – who, following her father’s departure for the priesthood, was left to deal with the loss of two parents in quick succession – the good shepherd continues to tend his wayward, eccentric and exasperating flock, knowing that one is the mysterious confessor set on spilling his blood.

With a tongue as sharp as cheese wire, chewing hungrily on the nourishing dialogue, but softened by deep, compassionate gestures, it’s hard to think of Gleeson in better form. His composure as he marches on towards his reckoning is mightily impressive. It’s reminiscent of his turn in McDonagh’s brother Martin’s comic gem, In Bruges; I half expected Colin Farrell or Ralph Fiennes to pop up at any moment as the would-be killer.

Overall, McDonagh has plumped for and executed something that is effective almost to a fault. While I can’t help wonder if it would work better on the stage, there is no denying that Calvary is an incisive, thrilling and original piece of work. Packed with an abundance of distinct and amusing characters, coupled with penetrating insight, it might just be the best McDonagh film, and that’s saying something. I’ll have to watch it again and see – with McGahern stashed away on the bottom shelf for good measure.

Calvary is showing at the Barbican Cinema, Beech Street, EC2Y 8AE until 24 April.