Since moving to London in 1981, Phil Maxwell has always lived just off Brick Lane in an 11-storey tower block. It is the perfect location for somebody who is known as the photographer of Brick Lane and its surrounding areas. “I’ve noticed how the London skyline changes over the years,” Maxwell says.

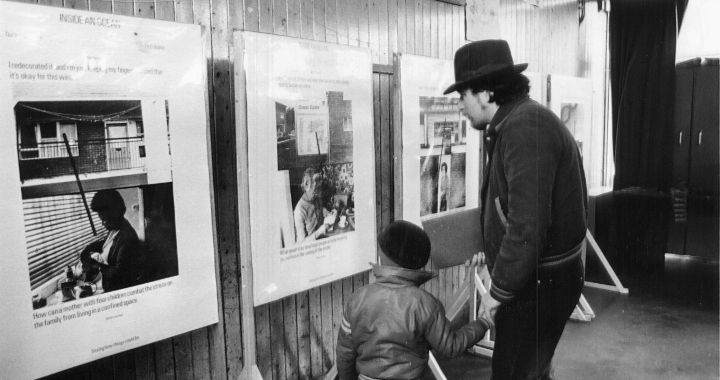

These changes are documented in Maxwell’s new book Brick Lane by Spitalfields Life Books, an intimate collection of photographs dating back to 1982. The book dispenses with words to let the photographs speak for themselves.

His passion for documenting the inner city began in Toxteth, Liverpool, a place that, Maxwell says, “wasn’t too dissimilar to Brick Lane”. Maxwell admits he is particularly fond of his photographs from the 1980s because the “environment was so disconnected”. Maxwell adds: “The area had lots of corrugated iron, dilapidated buildings and that somehow enabled me to focus on the people better.”

Maxwell’s photography captures moments of humanity that are apparent in all three decades. “There’s a similarity in the faces and a common humanity which I’m interested in capturing in my work,” says Maxwell.

However, Maxwell has been witness to a lot of change in the area since 1981. Maxwell says: “When I moved here, it was quite run down but now it is a playground for people who can frequent the bars. A lot of people have been driven out of the area. I preferred it before it became commercialised like it is now.”

This change has not dampened Maxwell’s enthusiasm for the area. The older photographs are special, Maxwell insists, because it shows how Brick Lane used to be a meeting place for Bangladeshi families. “The houses were quite overcrowded, so people treated the street as an extension of their home. It’s like a theatre where all human life is there.”

Asked if the area bored him, Maxwell says: “I never get bored of the area. If I walked out and took a photograph now, there’d be something new for me. It constantly surprises me.” Against a backdrop of change, Maxwell finds interest in the faces of Brick Lane and its surrounding areas.

“It’s interesting to see the different characteristics and personalities on Brick Lane or in Whitechapel and Stepney,” Maxwell tells me. Brick Lane is a crossroads between the city and the “real east end” with people on lower incomes. His photography thrives on the hustle and bustle of the marketplaces, the interaction between people from different cultures and the faces of the people.

When asked if his work was political, Maxwell replies: “It is insomuch that it values the lives and the tribulations of ordinary people. They came together to demonstrate against the war and the BNP and National Front in the 80s and 90s. I celebrate the people and their lives, and the difficulties they have in trying to survive.”

Maxwell’s book is a heartfelt look at a city and, most importantly, its people. “A lot of our culture celebrates celebrity. I think it’s important to show the other side. I am full of admiration for ordinary people and I want to celebrate them in my work.”

Maxwell’s work shows the change in our city, but also celebrates the undimmed enthusiasm of ordinary people trying to survive in London.

Brick Lane by Phil Maxwell on at the Mezzanine gallery, Rich Mix, 35 – 47 Bethnal Green Road, E1 6LA until 26 April.