What lasting benefits did East Londoners seek from the 2012 Olympics? What were we promised? What have and will we receive? These are questions that have been pondered ever since planning for the Games started in 2000.

Sixteen years and two mayors on – and four years after the Games themselves – it is possible at last to begin to take stock and patch together a verdict.

The London Olympics were from the start sold as an opportunity to regenerate East London in a sustainable and inclusive manner.

In 2007 Tessa Jowell, then minister in charge of this mega-event, promised to “make the Olympic Park a blueprint for sustainable living”.

Mayor Ken Livingstone, for his part, maintained that “the most enduring legacy of the Olympics will be the regeneration of an entire community [East London] for the direct benefit of everyone who lives there”.

Little by little, however, many of the idealistic goals that motivated those involved the early phases of legacy planning were eroded in the face of a sharp economic downturn, government cuts to public spending and a change in the political complexion, first of the London mayor and then of the government at Westminster.

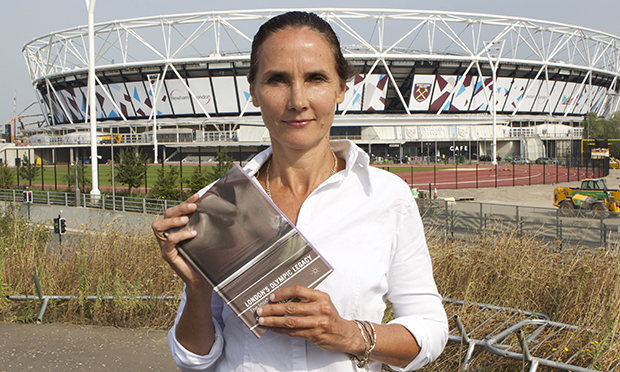

Gillian Evans’s volume London’s Olympic Legacy: The Inside Track provides an account of this process based on participant observation.

Though Evans – an academic anthropologist at the University of Manchester – has published the book with an academic imprint, it is written in an engaging narrative style as a chronicle of her insider view of the planning process.

Evans was embedded in the bodies responsible for legacy design from 2008 to 2012.

She recounts both the ebullience and commitment of those involved in developing plans for the Olympic Park and surrounds after the games, but also their frustration as governing structures (‘delivery vehicles’) changed and swerving political priorities unstitched years of work.

Though the volume is compelling in the dramatic style of its presentation, which is quite atypical of most academic monographs, it is in many ways an intensely frustrating book, as it reads more like spruced up field notes than a coherent analysis.

The study lacks the conceptual framing that might help readers make sense of the broader social and structural forces that shaped the evolution of legacy thinking, or the norms and role understandings that informed individuals’ visions of what they were trying to achieve.

Another underwhelming aspect of the volume is that the main narrative ends abruptly in 2012, before legacy delivery had got underway in earnest. The brief ‘afterward’ provides a sketch of the some of the achievements and failures of the delivery process, but not an overall assessment of the extent to which the original promises were kept.

This worm’s-eye view of someone working alongside Olympic legacy planners has produced invaluable documentary evidence of the evolution of thinking about how East London could and should be reshaped in the post-Olympic period, but it would have benefited tremendously from more in-depth analysis.

London’s Olympic Legacy: The Inside Track is published by Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN: 978-0-230-31390