“I’ve grown up always going for walks,” says Alice Stevenson. Having grown up in West London, Stevenson has walked the city for years and is now an East End resident.

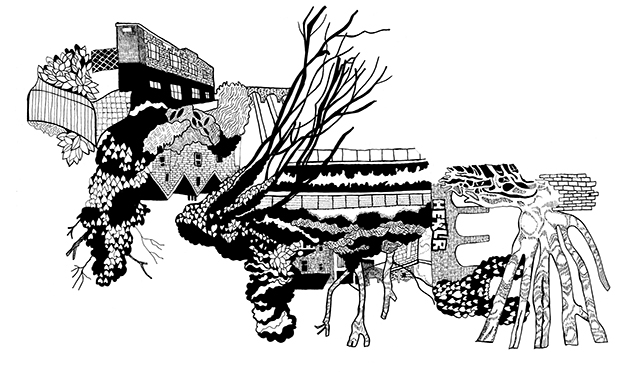

Ways to Walk in London is her first book, and it came as a surprise to Stevenson, who primarily identified herself as an illustrator. It’s a collection of personal journeys across the capital, with the text complemented by her distinctive illustrations.

Stevenson sees London not just for its historical importance but for its unique atmosphere too.

Stevenson says: “Woolwich felt so remote and industrial, with these brutal, abstract structures and when I reached Greenwich it felt different, like a seaside town – maybe it’s because of its maritime history. It was such a contrast.”

Ways to Walk in London takes us to places such as the Isle of Dogs, Shadwell Basin and Hackney, and to the reflective surfaces of Canary Wharf. “I like how you can have all these different experiences in the same city,” says Stevenson.

The book doesn’t just focus on the physical side of the city though. Stevenson sees the process of walking as a vital source of artistic inspiration: “Walking makes really good memories,” she says. “When you’re on public transport and it’s busy, you don’t have time to sit back and observe things or think about how something feels. I think walking your life slows down. You start noticing things you wouldn’t physically have time to do otherwise. I find it very inspiring, visually.”

Stevenson sees a crucial difference between walking alone and walking with friends: “I feel when I walk by myself I become really fixated with details and notice things a lot more, whereas with a friend, you can talk to that person about the walk, which made it easier to work out. When I did walks on my own, it was tough to find out what the walk was about.”

Part of the book’s success is that the text is filled with keen observations and only the necessary historical details. Stevenson didn’t want the book to be a list of places and historical facts, but a document of her personal wanderings.

The text is stripped back, and Stevenson says she enjoyed the challenge of working to these limitations: “It forced me to physically edit it and stop it from rambling. I could’ve written hundreds of pages about these walks. For me, I’ve always admired minimal writers, which I think has something to do with being an illustrator, working with limitations.”

Stevenson’s book is a fetching tribute to walking, and to London. The book shows the city in all its beauty and contradictions and in all its details – the bare oaks of London Fields taking on a new “spectre-like dignity” in the fog. Stevenson’s passion for the city is infectious and the book is a good place to start for anybody thinking of exploring London further on foot.

Ways to Walk in London: Hidden Places and New Perspectives is published by September Publishing.

ISBN: 9781910463024 RRP: £12.99