According to Stoke Newington writer and historian Lee Jackson, the funny thing about the smoke, fog and grime in Victorian London was how people seemed to love it.

“There are so many quotes about ‘dear, dirty old London’,” Jackson says. “They’ve got that sort of indulgence for the filth and the grubbiness of it, because it’s so distinctive – distinctively urban.”

Jackson has just spent two years researching such delights as cesspools in the 1860s, and has sifted through the account-books of rag-and-bone men to write the book which takes its title from such affectionate sentiments.

Dirty Old London: the Victorian Fight Against Filth is the story of a forgotten world, a world in which it was normal for the streets to be two-foot-deep in mud, for hats to turn black simply from being worn outside and for tap-water to be deemed drinkable as long as the half-glass of brown sediment it contained had sunk to the bottom.

One of the book’s achievements is to enable the imaginative leap required to understand that these conditions were once accepted as the status quo. His prose forms a well-sprung surface from which the reader can make this jump into the past, recording the development of everyday amenities like paved roads and the collection of rubbish which it is easy to forget are ideas someone once had to think up.

It’s a gripping tale which pits diligent reformers and wacky idealists against the literally parochial governing authorities and the stubborn refusal of the middle classes ever to pay for any kind of civic improvement.

“It’s that very sort of Victorian, 19th century, laissez-faire sort of thing; small government,” says Jackson. “And the whole book in a way is about that sort of thing: what does it mean to have local government?”

Dirty Old London answers the question in such an intriguing way that you start to wonder why people don’t ask it more often. Household waste, for instance. At the start of the century, the collection of ‘dust’ – predominantly made up of ash from fireplaces – was a jealously guarded privilege awarded to private contractors, who paid local councils high fees to be allowed to collect it.

Ash had value as it was used in the manufacture of bricks. There was a colossal demand for bricks at the time and, in consequence, for ash. Several ‘dust men’ became extraordinarily wealthy from the trade, including Henry Dodd, an Islington rubbish merchant who left an estate of £111,000 when he died in 1881 (a fortune that in today’s money would be comparable to that of J.K. Rowling).

But the dust trade was a victim of its own success. London grew too big, and the ‘brickfields’ in which the East End was baked were moved further away from the centre of the city. It became less and less economical to cart dust out that far, and bricks imported from Birmingham offered too much competition.

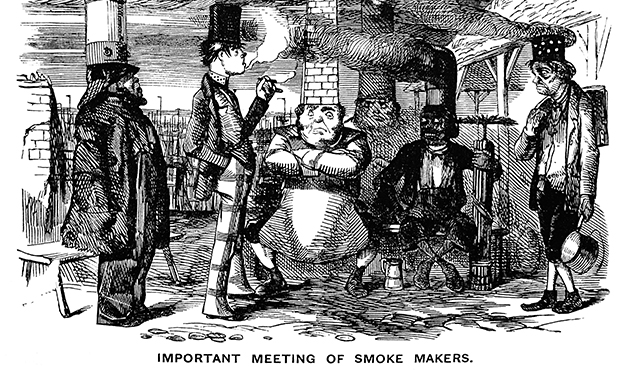

London was also ‘the Smoke’ – “a city named after its own pollutant”, as Jackson puts it. Fog was only part of the problem, but an all-enveloping part. It had a certain allure, and featured prominently in the erotic anecdotes assembled into the anonymous pornographic memoir My Secret Life, as well as in popular magazine stories about low-vis romantic encounters of the sort that – in Jackson’s words – “end with people turning round and saying ‘didn’t you know that was the Countess Von Such and Such you were speaking to!’”

Mud was also pervasive. Most of it was horse-dung, mixed with general filth and sewage to form an omnipresent ooze. As with the brickfields, farmland became so far away as London developed that it was no longer worth anyone’s while to crape the mud off the streets and sell it for fertiliser – the system the city had relied on to keep its streets navigable.

Crossing-sweepers – familiar to readers of Dickens as the ragged objects of benevolence, cruelty and non-standard orthography (such as Jo in Bleak House, whose every ‘v’ is written as a ‘w’) – didn’t simply keep junctions looking tidy as their name might suggest, but were actually in charge of ploughing a thoroughfare or ‘crossing’ through the mire and keeping it clean so that people could get from one side to the other, relying on optional tips as payment for the service.

Jackson’s enthusiasm for this stuff stems from his days as a Victorian crime novelist. His research ran away with him and now he predominantly writes history. He is the man behind the online archive of historical documents Victorian London, a website so popular that it’s listed first on a Google search for its name, beating Wikipedia and the several museums and tour operators also competing for the term. “More people have read that website than have read my books, I’m sure of that,” he reflects.

Jackson works on the period because of its continuing relevance. “It’s the cusp of modernity,” he says. “Transport. The Victorians thought you could annihilate time and space with the railway – you can suddenly move from one city to another in a couple of hours, the real modern transition.

“The Victorians invented rollerskates, you have these wonderful photos of women in their bustles rollerskating around on rinks made of marble.”

The washing machine, of the handle- operated kind, was also a 19th century invention, marketed using what Jackson calls “these amazing 1950s-style adverts. One was like ‘my servants wash more in three days than they used to in three weeks’, or ‘the boys in the reformatory now do their laundry much better than they could before!’

“By the end of the era you have the cinema, the radio – it’s all there. There’s very little in modern life whose origins aren’t Victorian. The crux of modern life is Victorian, for me.”

Jackson was born in Manchester and has lived in Stoke Newington for the last twenty years, an area which he says “started off as a very pretty village, and its first boom was as a rural retreat for bankers from the city.

“Then people realised they could make a lot more money by buying the fields, digging up the clay and building houses.”

He sees the social changes in Stoke Newington over the time he has lived there as “an exact parallel with Islington in the 1980s”, with gentrification and rising house prices. “I find it a bit depressing in a way how you just see wealth knocking people out of the way – and I’m part of it.

“But no one owns any district for a long time in London – with the possible exception of Mayfair, which is literally owned by the Grosvenor estate. The beauty of things like Hackney and Islington is there aren’t these overweening vast estates. This has changed over time, and if there is an economic collapse it’ll all change again.”

At a time when the idea of collective projects for the common good has once again become unpopular, it’s good to be reminded that it was only recently we managed to climb out of our own filth.

Dirty Old London:The Victorian Fight Against Filth is published by Yale University Press. RRP: £20. ISBN 9780300192056