Following Skepta’s Mercury Prize win, 2016 could be seen as the the year that grime came of age.

Grime isn’t just about music: for a whole generation, this is a definitive lifestyle and culture. Back in Bow in the early 2000s, however, the artists who would go on to be considered as the founding fathers of grime weren’t expecting much.

Though it seems almost surreal to think of them in this way now, most of grime’s big names were just school friends in East London’s council estates, messing about in their free time.

With This Is Grime journalist Hattie Collins allows for a fascinating, unprecedented behind-the-scenes look at the musical revolution that has defined a generation.

It is an impressive compilation of interviews with the key figures involved and, of course, there’s no one better equipped to be telling the story of the scene than the people at the centre of it all (especially given that Collins speaks to fellow journalists too, allowing for a degree of outsider commentary).

In many ways it’s more of a sourcebook than anything: you can imagine in all future think-pieces and books on grime, This Is Grime will provide a wealth of the references and key quotes.

The book intimately charts the timeline of grime: born out of jungle raves and pirate radio, and the years that saw it rising to its current dominant state, via backlash, violence, and mainstream recognition.

There’s conversations with some of the up and coming names in the scene alongside the hallowed fathers Wiley, Dizzee and Kano. And, of course, there’s a look into the sensational rise of the Adenuga family (aka Skepta, JME and Julie).

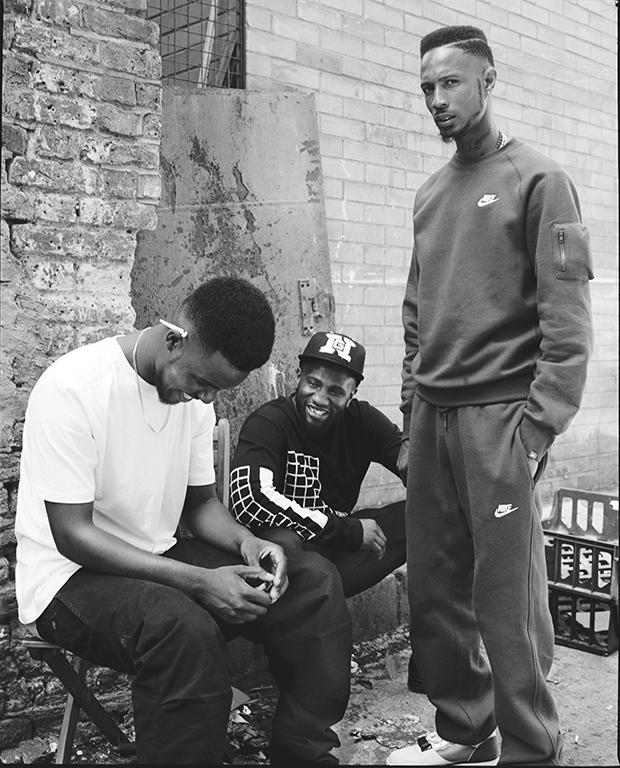

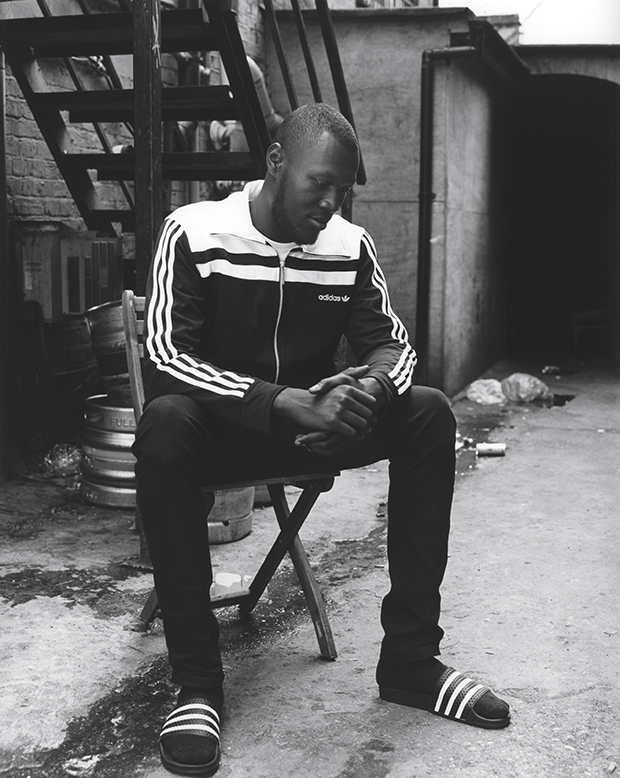

The accompanying photographs – taken exclusively for the book by Olivia Rose – are wonderfully atmospheric, and add to the visceral nature in which the story is told.

In allowing the book to be told solely by the interviewees, Collins has allowed for a refreshing open-endedness at some points: for example, at the beginning of the book many MCs and producers say that grime could never have happened without the UK garage scene, which heavily inspired it.

For others, grime was more of an aggressive reaction to the perceived pomposity of garage.

Like the music itself, things aren’t sugar-coated in the book: the artists don’t shy away from the reality of stabbings and disaffected youth. In the past, UK politicians have voiced an unease with the style, fearing a glorification of violence (though is hard to not consider this fear as at least slightly racially motivated).

But the artists make the valid point that grime was born out of their reality: that the music gains its raw energy in channelling those aggressions.

Crazy Titch, in his taking down of garage, points out that the scene was unrelatable: rather than songs about champagne and fancy cars, grime was the not-always pleasant truth about the ends they all grew up in.

The interview-style of the book does at points make you want some actual narrative from someone not at the centre of it all, and at times you even crave a documentary: it can feel the equivalent of reading a script rather than getting to watch the play.

Overall, though, it’s a wonderful, intricate snapshot of an immensely important movement in British culture. It perhaps doesn’t offer much to those without a basic awareness of the scene, but for most who are interested in the story, This Is Grime has a lot to offer.

In a musical landscape largely dominated by beige pop, grime has injected the sound of something other into the British scene: something exciting, different, and completely local.

This Is Grime captures the thrill and disbelief driving the movement so far, and is endearing in its candid insights into the past decade.

What makes the book particularly exciting is the knowledge that there’s still plenty to come from the scene. To quote JME: “It’s only the end of the beginning.”